We were racing the sun, and trying our best to avoid the moon.

My partner and I were climbing in the Verdon Gorge, six hours from our home of Chamonix France. August is peak tourist season in the area known as the Grand Canyon of Europe. All summer long, families flock to the deep slotted canyon-hiking, canyoning, and visiting the 12 century chapel situated near the rim of the gorge. August is a bad time for climbing with high heat and the sun’s intense gaze. But it was the only time we had, and my partner, Pierre, wanted to share one of his favorite parts of France with me.

On our last day, we found ourself repelling down into the gorge at 4pm-usually the time I’m trying to wrap up my day’s activities. We would have five hours to climb 11 pitches back to the car before the sun set and headlamps would become mandatory. We set off from the bottom, easing into a smooth rhythm- swapping pitches and gawking at the view of the river below us at each belay station.

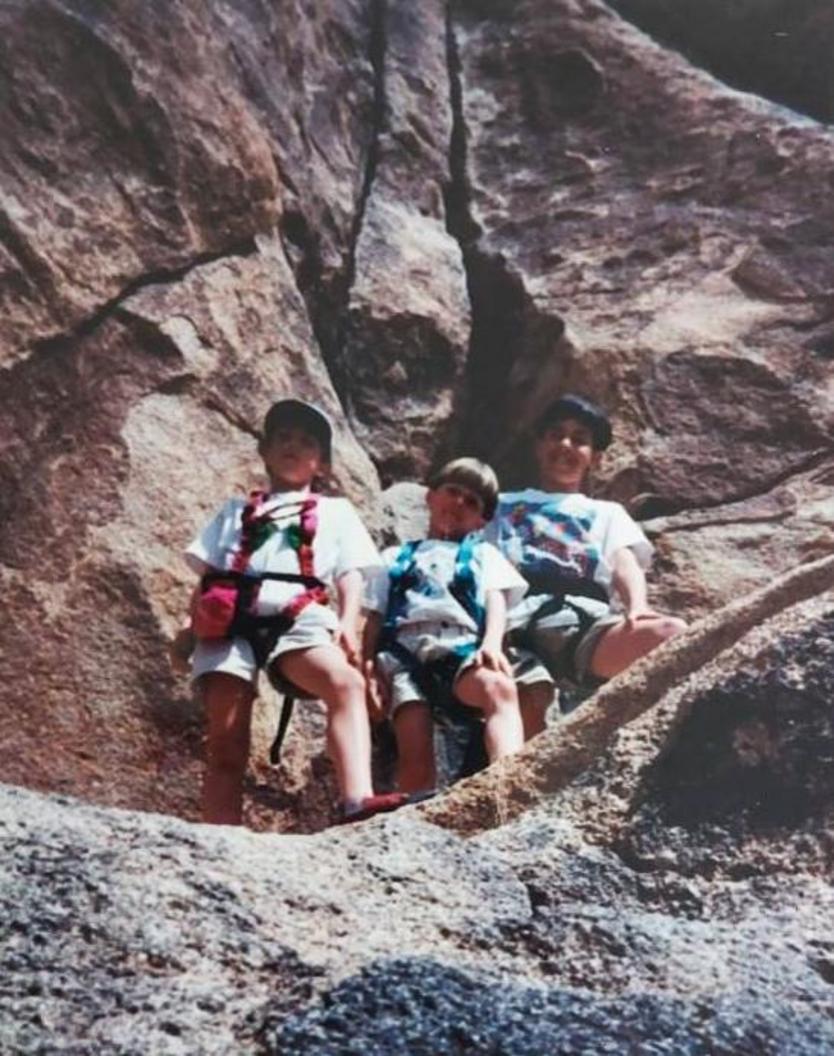

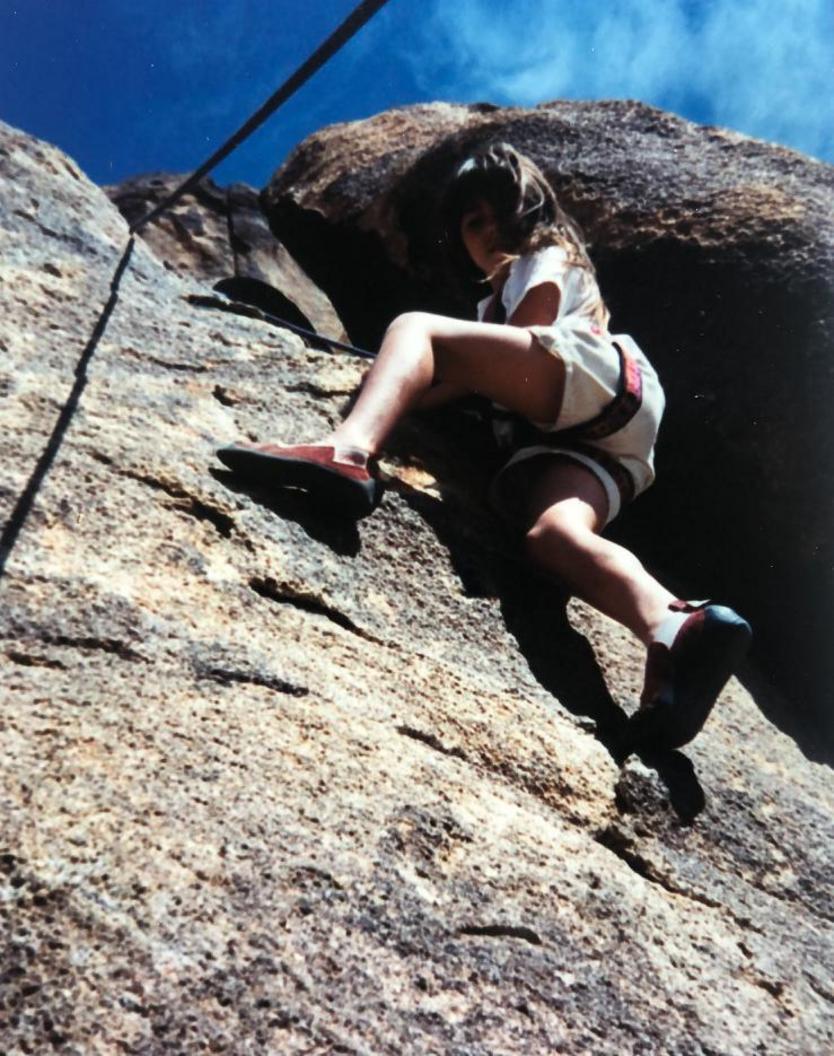

I started climbing at a very young age. The exact date and place is unknown. Most likely it was in Wyoming, where I was born and raised. Since there were full body harnesses involved, I’m sure it was under the age of seven. My parents love of climbing and the outdoors naturally spilled over to my two brothers and me. Going climbing was not so much of a choice as it was an assumed part of our lives. I don’t remember ever asking to go climbing, nor do I remember ever complaining when we did.

Warm weather weekends and holidays found the five of us piled into the family’s ’94 black and red Chevy Suburban driving to numerous crags in the Mountain West. Spring break at Joshua Tree. Summer camping in Yosemite. Autumn weekends scrambling up bulbous stone formations at City of Rocks in Idaho.

Our parents let us run wild and loose. It was the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. It wasn’t unusual to find my brothers and I crouching on the summit of a boulder near nightfall, our parents out of eyesight preparing Top Ramen for dinner. The rocks were our playground, the sky our babysitter.

My participation in climbing has ebbed and flowed since those days. Soccer, volleyball, skiing and hormones replaced climbing in middle school and high school. I picked it up again in college as an easy way to make friends while being 2,419 miles from home. When I moved to Washington, DC, for my first “real” job; climbing (as well as all other forms of exercise and movement) fell aside yet again.

At the age of 25, I traded my stable job in the hospitality sector for the dream and instability of becoming a professional skier. While my parents taught us to seek beyond our limits, I think even they were surprised by my bold jump into the world of professional sports. I graced very few podiums during childhood athletics. I warmed a lot of benches for soccer games. My box of childhood mementos had more participation awards and stellar report cards than trophies or medals. Yet the activity, the community, the call was all more appealing than the corporate track I had found myself on.

I loved the challenge of getting better at skiing, at getting better at moving. It took years to learn all the techniques and tricks I needed to be the best skier, but throughout the process I felt the familiar feeling of contentedness, of personal expression found playing outside.