BIKEPACKING B.C.’S FAMED LOWER SUNSHINE COAST

“Cyclists board down by the black fence. Follow the signs for pedestrians. Ferry loads at 4:30. I’d be down there around 4:20 if I was you.” The ticketmaster winks at me behind a smudged pane of plexiglass. “Not a bad time to be in Canada, eh?”

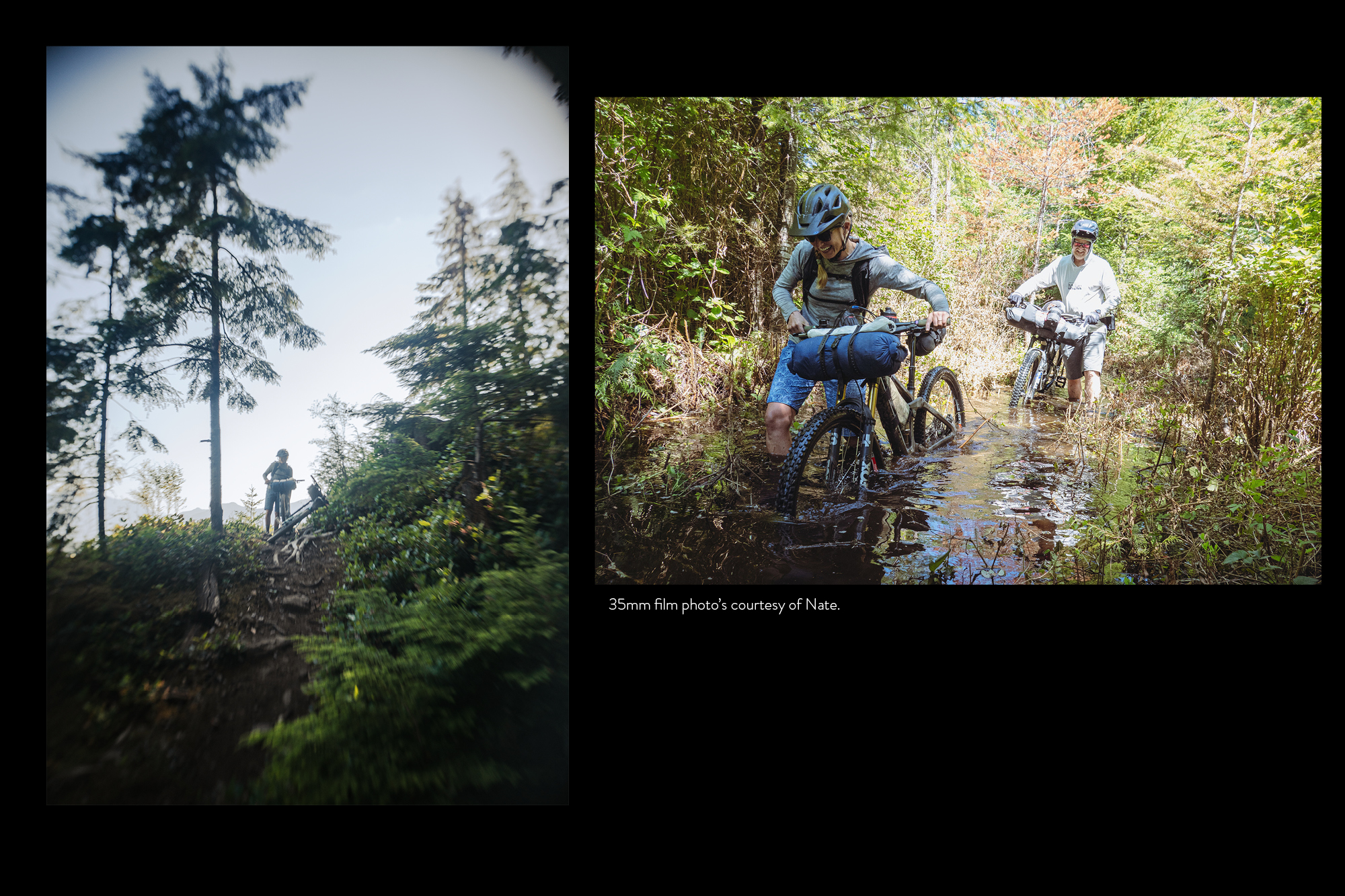

He slides two ferry tickets through the notch in his cubicle. My friend Nate Shearer chuckles. We take our tickets and wheel our loaded mountain bikes out onto the streets of West Vancouver.

It’s a white-hot Friday afternoon in mid-July and summer is in full swing. Streams of tourists and second-home-owning Vancouverites swarm the sidewalks that wind along Horseshoe Bay waiting for their respective ferries to Nanaimo, Bowen Island, or Langdale. Nate and I are bound for Langdale, a small village on the southeastern end of the Sechelt peninsula and B.C.’s popular Sunshine Coast. Stretching for 112 miles through Tla’amin, shíshálh, Coast Salish, and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (or Squamish) Nations’ land, the Sunshine Coast is technically connected to mainland B.C. but is only accessible by boat or floatplane. It is precisely this remoteness—and the vast network of singletrack that traverses through it—that has lured me and Nate 3,000 miles northwest from our East Coast homes to the fjords and mountains of B.C.

It is precisely this remoteness—and the vast network of singletrack that traverses through it—that has lured me and Nate 3,000 miles northwest from our East Coast homes to the fjords and mountains of B.C.

Born and raised in the shadow of Washington, D.C., Nate has lived many lives during his 51 years on Earth. He’s apprenticed with fundamental Christian welders, delivered documents to U.S. senators, and styled runway models’ hair for high-end fashion shows the likes of Vera Wang. But all of that has come second to his first true love: the bicycle. From BMX racing to bike polo, Nate has spent the better part of five decades riding every style of bike on every type of terrain. His lifelong love of the sport became the subject of a scrappy video we filmed together in the fall of 2022 and entered into Presents, Freehub Magazine’s mountain bike film festival. When Nate and I learned the magazine had accepted our five-minute documentary short into the film fest, we decided its Bellingham premiere was the perfect excuse to piece together a B.C. bikepacking trip.